Sword & Sorcery vs the Book of Mormon

the sex appeal of hunky prophets in kilts can be plausibly denied

One of my favorite guilty pleasure movies is The Beastmaster. Like countless others of my age, I watched it on TV as a boy - not on HBO ("Hey, Beastmaster's On!"), since we didn't have it - probably on TBS ("The Beastmaster Station"), which means the boob shots were edited out and I didn't know what I was missing until I rediscovered it in my middle age. We probably taped it off TV, and I don't expect that my mother was very impressed by it, as she was not very impressed by the music videos on MTV which we spent most of the summer of 1987 watching, despite my parents' attempts to block Channel 14 from the remote control. That's another story.

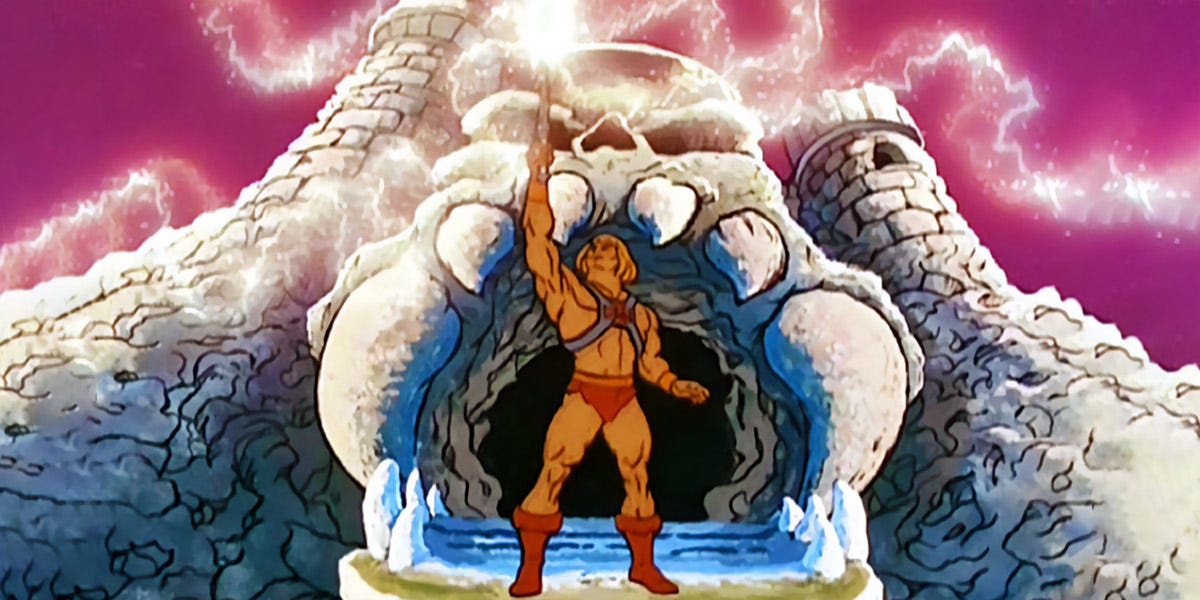

Beastmaster is one of several strong anchors in my life that keep an affection for Sword & Sorcery burning bright in my heart, even though I have only read the barest minimum in the literary genre and have gone years at a time without visiting. The real foundation for me was He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, which was my favorite boyhood cartoon show (along with GI Joe). I thank God that I spent my formative years watching animation of a muscular man in a loincloth with a sword saving the day while being magnanimous and kind-hearted.

There was a downside to this: spending so much of my time watching TV exacerbated the weight problem I struggled with throughout my childhood and which has persisted throughout my life. When I was a Boy Scout I had a subscription to Boys' Life magazine, and I don't remember exactly if it was in the ad section of that or of Popular Mechanics (probably both) that the Charles Atlas fitness ads enticed me with more presentations of a muscular male physique. As a Boy Scout I did get outside and go on hikes, though I also suffered the humiliation of failure while attempting the Tooth of Time at Philmont at age 13 due to my poor shape. So although I did have some victories of physical achievement, such as conquering Timpanogos at age 11, I never really crossed the great divide between daydreams of somehow magically being a strong man, and actually doing what would have been required for me to "slender down and muscle up," as my father once put it.

The thing about Marc Singer's performance in Beastmaster is that he's not as bulky as He-Man, or as Arnold portraying Conan. Watching the movie again I realized that one of the many things I like about it is that its idealized presentation of the athletic male body looks more realistic, more moderate - anyway, more plausibly within my reach. There have been a couple of times in my life when I actually managed to achieve a desirable weight and was reasonably physically fit. I didn’t even get to Beastmaster level, but at least I was slender. Recently I've been riding my bike for an hour five times a day, going to morning exercise classes an hour long one to two days a week, and trying to get out and hike with some kind of frequency. At my age, the benefits of this change in lifestyle take frustratingly more time to show than they did 20 years ago, but I hold on to hope that I might once again be able to go shirtless without shame.

There are other things I love about Beastmaster - besides, of course, the cute ferrets: the desert setting with its architecture vaguely reminiscent of ancient America, and the inclusion of the character Seth. These things reveal the disingenuousness of recent squawking about the fantasy genre's problematic lack of racial diversity, and also exemplify the flavor of Sword and Sorcery which I've always seen as akin to Orientalism in a way: a celebration of the exotic from the point of view of its chief authors and audiences. That's a separate complaint, I guess: it's not enough to portray and admire exotic settings and people, it's problematic to consider them exotic? Anyway, in the years when I was doing NaNoWriMo, the fantasy fiction forums routinely hosted the familiar ritual of lamenting how stuck the genre was in medieval Europe. That's also disingenuous. Like the hand-wringing over how racist our society supposedly still is, it's a bid at a turn on the Rameumptom of social virtue.

Speaking of the Rameumptom...

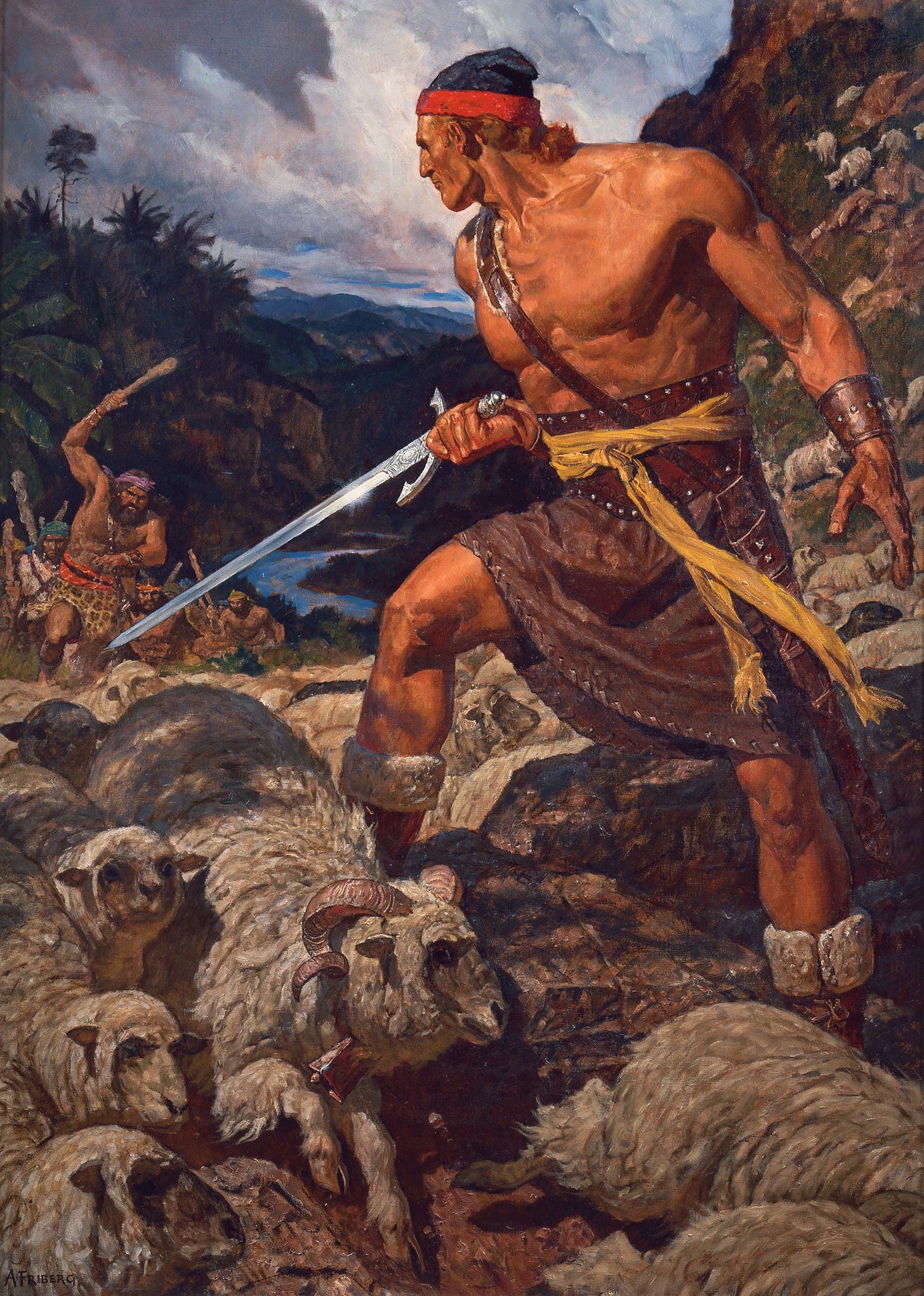

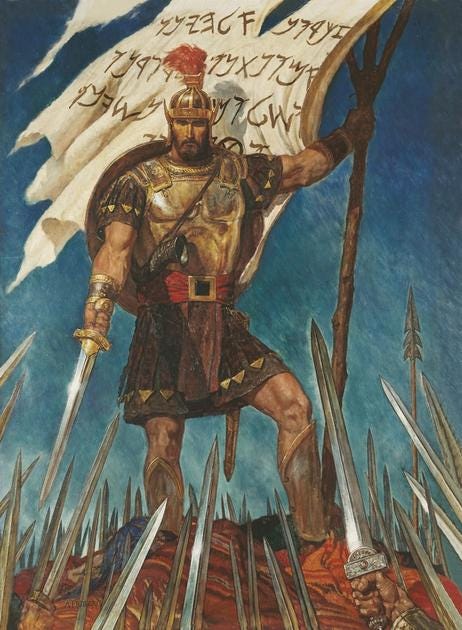

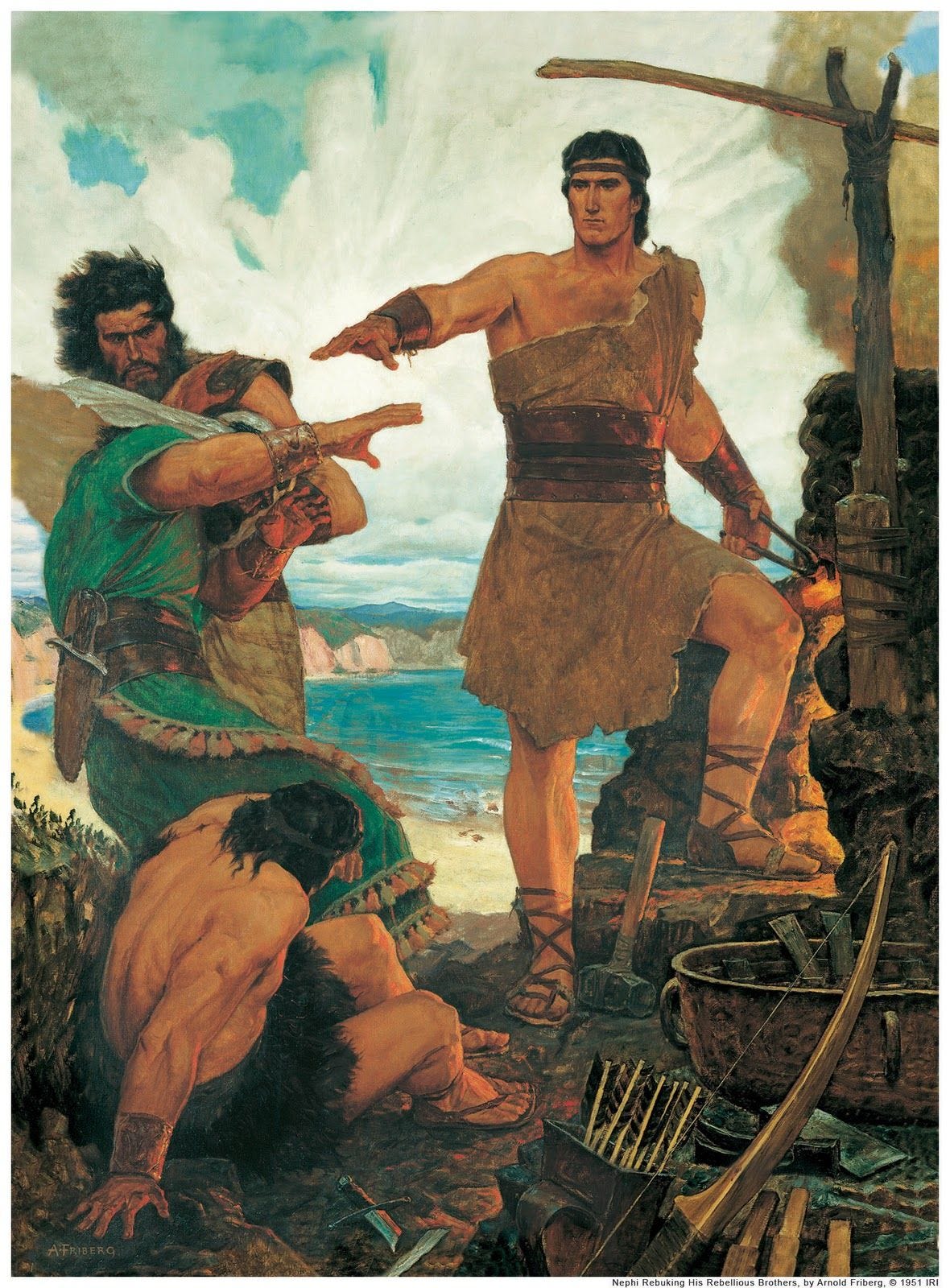

I don't know why it took me so long to take notice of the obvious similarities in the display of masculine strength and beauty between Sword & Sorcery movies and TV shows, and Arnold Friberg's paintings that appear in the Book of Mormon. I blame growing up in the 1980s, when the advertising industry did its best to lever the generation gap between teenagers and parents as wide as possible, and to make a disgust with anything older than 10 years seem an immutable law of human nature. Maybe my own personal defects had something to do with it too, but I would not have readily seen the continuity between the proud display of the human body in historical epic movies of the 1950s and fantastical movies of the 1980s, nor between stories of cowboys, lawmen, detectives and explorers in pulp magazines and the cocky heroes in the cockpits of their spaceships in the movies that thrilled me as a boy. The world was being made anew, and to acknowledge continuity with the past would mean deigning to give credit to the passe, the embarrassingly out-of-fashion. This went for music too.

And when it came to something like the Scriptures, even though I did read through the simplified and illustrated retellings of them that the Church put out before I started reading the sources on my own, still there was a sense that what happened in the Scriptures happened behind a layer of both seriousness and staid sacredness. So, although I formed strong impressions and visual associations of Friberg's portrayals of muscular, heroic-looking prophets, I didn't look at them the same way as I looked at He-Man or the Beastmaster. Which is a pity, and is something I want to change in my own life, at least.

It's been remarked that during some periods of Church history, people didn't take the Book of Mormon as seriously as it merits, rather regarding it as a collection of semi-romantic tales akin to the Arabian Nights. I'm glad for the emphasis President Benson made, when I was a boy, on the importance of the Book of Mormon and the need to take it seriously. I don't see how that has to stop us from having fun reading it by calling forth similar thrills in its episodes to the thrills we get from Sword & Sorcery media. I hope I'm not alone in this; I trust I'm not. So where are all you guys? And why aren't there more of us? Well,

The fantasy-reading subculture has grown hugely in the larger LDS culture throughout my adult life and the reasons for that are another story. But even here, Sword & Sorcery has the reputation of being lowbrow, even cheesy and trashy. The Book of Mormon, of course, is Scripture. Scripture, to paraphrase a satirical song I once heard, "is something good for you, like liver, spinach, and beets too." I have my share of emotional scars from my religious upbringing that made Sundays, Church attendance and Scripture reading into chores and associated them all with discomfort and boredom. People have left the Church for less, but I’m not about to go on some flattering podcast and wring my hands about the "religious trauma" of my upbringing. But thank God I discovered for myself the blood and thunder of Scripture, the swing and fuzz of human expressions of Divine experience, and yes, the fun. Maybe it's better to say: the mystery, the sense of ancient enchantment - aye, even the mythical. Maybe especially that.

In fantasy fiction generally (and I insist on a radical difference between Tolkien's mythopoetic fiction and the genre of fantasy as it has been established for over a half a century), magic is more or less mechanical, an extension of the laws of physics in the universe the author imagines. The miraculous events reported in the Book of Mormon are, well, just that: miracles. Stories of miracles feel and behave differently than the "magic systems" of the codified Fantasy genre. As Scripture, the Book of Mormon is closely related to mythology. So is Sword & Sorcery: the bombastic tone of the mythologizing unconscious which Jung pointed out has echoed consistently enough throughout all kinds of fantasy that its degradation or parody in the silliest manifestations of Sword & Sorcery is one of the genre's most recognizable caricatures. That bombastic tone happens to agree quite well with the Early Modern English so happily preserved by the enduring popularity of the King James Bible, so that Heavy Metal, with its considerable overlap with Sword & Sorcery, routinely draws inspiration from the Bible. And when it works, it really works.

But:

Our universe, where some of us believe in miracles and read about them, even if we have never seen some of the most famous kinds; and a universe where the laws of physics extend to the manipulation of matter by magical means irrespective of individual righteousness or Divine will - where conjuring objects out of thin air or zapping enemies is done with the same moral neutrality as anything we can do with our tools and technology here - these are radically different. Also, one of the defining traits of Sword & Sorcery is that the protagonists of the stories don't have to be moral paragons or even particularly admirable characters at all.

Maybe the compatibility problems could be summarized thus: fantasy fiction and art are escapes into worlds of the imagination, requiring the suspension of disbelief. The Book of Mormon is a voice from the dust of a lost world, asking for the will to believe. Fantasy is the human imagination escaping from the confines of human history and the world we inhabit. The Book of Mormon is the human heart and mind trying to convey the reality of God's hand working within these.

And then of course there's the matter of the human body, and its display. Sword & Sorcery just wouldn't be recognizable without that. Friberg's portrayals of the muscular men agree quite well with the genre, but what about the women? The nearest thing we get to a real honey is that wet convert walking out of the Waters of Mormon.

There could be more. There's really no shortage of subject matter: that baptized beauty is one of a crowd of extras invented by the artist, with no explicit individual mention of more than one of their names. It would be easy to take any episode of history in the Book of Mormon where there is a group of people present and populate it with imaginary women as well as men. The text gives ready prompts to the imagination: how many times does the record report women taken captive in wars? How many stories could be interpolated of individual valor in rescuing them, and portrayed in visual art? Or what about the concubines of Noah's court, or the Lamanite daughters, or the harlot Isabel, or the Lamanite queen whom Amalickiah marries? I recently discovered Annie Poon's portrayal of the daughter of Jared dancing. That's a step in the right direction - maybe as far as anyone ought to go, since the playful style keeps the picture from being titillating.

And that, of course, is the problem we face if we start wanting to make pictures of scantily-clad women in portrayals of Book of Mormon scenes: isn't that lascivious?

It's not as if there's no precedent for sexy women in religious art. The Ten Commandments has Ann Baxter dominating the screen for a good chunk of the film in her diaphanous gowns, and it has that scene of revelry before the golden calf. And that's not even considering all those old paintings of the repentant Mary Magdalene. Whoo-boy.

And Nephi said unto them: Go to horny jail.

It's not lascivious to portray Nephi or Ammon looking like Conan, because the objectification of the male body in our habituated moral framework is not so obviously sexual. The reason for this double standard ought to be universally understood, but since it has been so much disavowed, let's go over it again:

Female choice is the linchpin of sexual reproduction. Humans inherit a complex embellishment of that base, firmly establishing women's mystery and allure and the female body as the focal point to normal human heterosexuality. Moralizing about the objectification of women or "the male gaze" will not change that fundamental fact of our existence and practically never helps in facing the truth, let alone knowing what to do about it.

Male displays, including of physical prowess, are secondary characteristics of human sexuality. Secondary sex characteristics would fain usurp our attention as if they were the definitive features, but they are not.

Therefore, hunky prophets in kilts are at a safe enough distance from the pulsating engine at the heart of human sexuality that their sex appeal can be plausibly denied or diverted. If the Arnold Friberg Book of Mormon paintings objectify their male subjects - and I say they do - then that's a reason they should be celebrated, and that we need more pictures like them. The objectification of men does not and cannot draw as much notice, sympathy or outrage as the objectification of women: men are meant to carry heavy burdens of all kinds and to like it. As for body image, it's a good thing for young boys to see examples of manly strength (which, again, is at a safe distance of plausible deniability from human sexual instinct), to have those role models to emulate. If young boys feel insecure or inadequate comparing their scrawny or chubby figures with the idealized figures in those pictures, it will probably do more good than harm. The Church has need of willing men to put their shoulders to the wheel, and it's far better to have some young men ashamed of their physical inadequacies than to enervate them en masse by allowing a misguided quest for "equality" to seduce us into treating them with the trendy solicitude of the counseling profession. We've had too much of that already. Body shaming men is not the only way to motivate us, but it is a goad that we ought to keep handy. The shame that keeps me from going shirtless in appropriate settings is righteous: a standard is there for me to aspire to, and to try to placate me by lowering it will not help me.

To bring the apparent digression back to the point: for anyone who is tired of the Arnold Friberg paintings, I say a good solution to it is for more Book of Mormon art featuring strapping hunks. Even better, do them in a style like Frank Frazetta. But I'm not naive: if we are blessed with a rising corps of LDS artists answering this call, we might have to resign ourselves with a lack of the female representation traditional to the Sword & Sorcery genre. It is probably not realistic to expect some enterprising artist to portray, say, Amalickiah's wooing of the Lamanite queen in the style of Frank Frazetta or Boris Vallejo, even though that would be totally badass.

The prospect may not be so austere as I fear: one of my favorite contemporary artists was a classmate at BYU, and she draws plenty of sexy women. Maybe I'll see about commissioning something from her. But if that doesn't work out, then I think we'll be ok.

Recognizing the radical rifts between Sword & Sorcery and Scripture, we can still have more grit, more fuzz, more fun, more kick, more juice in portrayals of the Book of Mormon. After all, this is a book that gives us tyrants, rebels, epic battles, perilous quests, ravenous beasts, and ancient relics. There's room for plenty more portrayals of all of this, plenty of room for works of the imagination that convey wonder, blood and thunder...

even (even if kept at arm's length) sex appeal.